PATROLLING THE BOUNDARIES OF TASTE

Many parents feel anxious but powerless over the media their children consume. Should anyone else share this burden?

After consulting with ten thousand people, including teenagers, the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) has issued new ratings guidelines to address rapidly developing norms in three particular areas: violence, sex and language.

Experiments apparently show that if a frog is left in cold water which heats up slowly to boiling point, its body does not register the incremental environmental changes until it is too late. Cultural changes feel similar: we do not remember accurately how things once were or appreciate how rapidly they change without us realising.

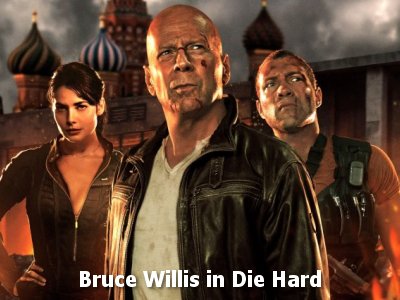

The Die Hard franchise offers a salutary example. The first film, a classic of its kind, was rated 18. Language undoubtedly played a part in this, but so too did repeated graphic violence as John McLane picked off the bad guys. The latest – many would say risible – addition to the canon of A Good Day to Die Hard was passed with a 12A certificate, meaning a child of any age could watch the film provided they were accompanied by an adult. The language was toned down but permissions were given over the violence because - though relentless - it proved less graphic in its detail. In other words, as long as the violence mimics a cartoon in the ability of people to get up and carry on as normal after extreme physical punishment, any child may see it like they would Tom and Jerry. We have come a long way in twenty-five years.

The population sample consulted by the BBFC shared this concern but there is unlikely to be a reversal in these kinds of ratings, not least because of the genre of superhero, post-human cinema, where special effects allow persistent, crunching violence as a form of fantasy.

Of greater concern to the public was the largely unregulated arena of contemporary music videos, freely available on digital TV or YouTube but which parents sometimes felt amounted to soft pornography. Recent stage performances by Miley Cyrus and Robin Thicke have brought these developments to a wider audience. Those without a finger on the pulse of such media (which means most people) would be alarmed at the degree of casual sexism children and young people are exposed to as they consume music

The BBFC sample was less worried by the use of bad language in films because of its routine use in daily life. The context of swearing rather than its frequency will become the BBFC’s priority in future, a move announced in the same week that Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street broke the cinematic record for the number of F-words (506 altogether, amounting to just under three a minute throughout a three hour long film). Most adults anticipate the use of swearing in a film and accept its role within parameters; it is not entirely clear where these parameters lie now that bad language is no longer deemed offensive.

The BBFC has said that it wishes to reflect societal norms rather than to try and change them. On one level this is a modest recognition of its limited powers; a small-staffed British outfit is not going to alter the surrounding culture even if it wanted to. However, it can set some of the boundaries in which public culture is experienced. The idea that it should only hold a mirror up to the public implies a lack of any inherent values with which to tackle one of the biggest challenges of our generation: how to help children and young people handle the deluge of media that heads its way. While once Christian voices in this area were traduced by mentioning the name Mary Whitehouse, there is evidence to suggest – not least in the BBFC sample – that many parents have underlying anxieties about the media their children consume and the effect it has upon the way they view the world.

The rapid emergence of new digital media which can be streamed on demand onto smart phones means regulation is much less effective than even a decade earlier. Amid these developments, no-one seriously challenges the media makers to demonstrate responsibility in the way music, art and drama are imagined. While some artists are careful not to stray too near the uncertain boundaries beyond which people – and especially children - may be psychologically influenced or even harmed, others show a reckless or provocative disregard for what their art may do. The erosion of shame which has marked our generation means this is only likely to continue.

POPULAR ARTICLES

Obama's Covert Wars

The use of drones is going to change warfare out of all recognition in the next decades.

Through A Glass Starkly

Images of traumatic incidents caught on mobile phone can be put to remarkable effect.

What Are British Values?

Is there a British identity and if so, what has shaped the values and institutions that form it?